Please visit our new site!

Humor

Nerdy verse

Poems for my scientific mind

27 May 2007

www.lablit.com/article/260

George Herbert finds favor

I don’t know whether it’s my scientific education or my Orthodox Jewish upbringing that engenders my love of rules in poetry

Last night in bed I was Taking off Emily Dickinson’s Clothes while Making Cocoa for Kingsley Amis. In other words I was dipping into two creatively entitled poetry collections by former American Poet Laureate, Billy Collins, and English National Treasure, Wendy Cope, respectively. The former, while tending less towards fixed-form poetry than the latter, was inadvertently the source of my introduction to the ‘paradelle’ a verse style that appeals to my scientific mode of thinking.

In his own words, Billy Collins describes paradelle as:

…one of the more demanding French fixed forms, first appearing in the langue d'oc love poetry of the eleventh century. It is a poem of four six-line stanzas in which the first and second lines, as well as the third and fourth lines of the first three stanzas, must be identical. The fifth and sixth lines, which traditionally resolve these stanzas, must use all the words from the preceding lines and only those words. Similarly, the final stanza must use every word from all the preceding stanzas and only those words.

While Collins uses the form ironically I took on the paradelle challenge with a vengeance culminating in the following effort to which I added various extra rules of my own.

Glutton for Punishment

I’m eager to write a good paradelle,

I’m eager to write a good paradelle,

And hopefully one could rhyme as well,

And hopefully one could rhyme as well,

Hopefully I’m eager, well and good,

To write, as rhyme, a paradelle – one could…Devised by eleventh century Frenchmen,

Devised by eleventh century Frenchmen,

Far south of the Loire, Aquitaine’s henchmen,

Far south of the Loire, Aquitaine’s henchmen,

Aquitaine’s Henchmen, the Frenchmen, by far,

Eleventh century, devised south of Loire.Sights not content with the challenge presented,

Sights not content with the challenge presented,

Sleepless nights spent, nesting rhymes implemented,

Sleepless nights spent, nesting rhymes implemented,

Presented sleepless challenge, not nesting nights,

Implemented spent rhymes, content with the sights.Sights of Aquitaine’s sleepless century spent

Nesting with henchmen, far well and content.

Nights by the Loire, presented with a rhyme

South Frenchmen, hopefully eager as I’m

To write paradelle rhymes, challenge the good,

Devised, implemented – not one eleventh could.

It’s a bit like doing sudoku although that craze has thankfully passed me by. I don’t know whether it’s my scientific education or my Orthodox Jewish upbringing that engenders my love of rules in poetry.

The common denominator characterising my favourite poets (who include Sophie Hannah, Dorothy Parker, George Herbert and too many others to name) is their allegiance to form. Triolet, Ballad, Ballade, Limerick, I’m easy, but I do like a little bit of structure to my verse.

A. S. Byatt wrote a linguistically exquisite essay (you can find it in Passions of the Mind) about her experience judging a Times Literary Supplement poetry competition. In it she argues that while the entrants had so much to say they were limited by their prior experience with language. ‘Free verse…,’ she says, ’unaware of the forms from which it has been “freed" …can be extremely depressing.’

Stephen Fry has attempted to set this problem to rights with his pedagogical labour of love, The Ode Less Travelled, in which many of my long-standing questions are answered. Here I reveal the extent of my nerdiness. How does one of the most famous iambic pentameters of all time (To be or not to be, etc.) get away with having eleven syllables? If you want to know, go and get the book. Meanwhile, I’m getting a lot of joy from the image of you counting them up on your fingers – you haven’t got enough (unless, of course, you are hexadactyl).

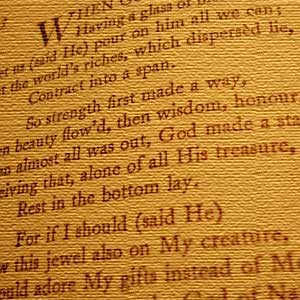

If you were hoping for a piece on ‘poems about science’ you’ll realise by now that you are in the wrong place. I have dabbled a bit with these, even going so far as to produce a conference poster entirely in verse, one sad panel of which appears below:

A good title for that slide might be ‘Why I made my career in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy’ (rather than poetry or crystallography – though I still hold out pathetic hopes for both). In the meantime, as I learn Betjeman by heart while sonicating E. coli in alternating pulses, I’ll revel in their respective rhythms.