Please visit our new site!

Essay

The literary Ada

In honor of Ada Lovelace Day, a round-up of fictional re-imaginings of the Victorian programmer

9 October 2018

www.lablit.com/article/949

Ada’s contemporary significance is as much about her imaginative potential in our lifetime as what she achieved in her own

Today marks the tenth anniversary of Ada Lovelace Day, an annual celebration of women, past and present, who have contributed to the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) fields. The Victorian mathematician Ada Lovelace was a flesh-and-blood human, best known today as the “first computer programmer,” for an algorithm she wrote in the early 1840s.

But Ada’s story also has a science-fictional quality. Modern programmers, fans, critics and writers have revived Lovelace to speak to our contemporary preoccupations, our current needs. She has become our modern creation.

As one character in Lord Byron’s Novel (2005) insists, Ada’s importance is less about “what she did do, of which the rather inconclusive records exist, but what she was, and might have been — which is more important to us, who live in the world she longed to glimpse — and did glimpse.”

In this sense, Ada’s contemporary significance is as much about her imaginative potential in our lifetime as what she achieved in her own. Ada has been re-invented, above all, to address today’s crisis of inclusivity and representation in tech culture.

Her reach, however, extends beyond the spaces of tech start-ups and girls-in-STEM non-profits. She has had numerous literary re-incarnations, most recently in Jennifer Chiaverini’s historical novel Enchantress of Numbers: A Novel of Ada Lovelace.

As much as these fictional portraits might obscure or romanticize the historical Lovelace, they also bring us closer to her imaginative vision. Lovelace was deeply interested in a synthesis of scientific and artistic ways of knowing. She even coined the term “poetical science” to describe this convergence. In 1843, she collaborated with her friend, the inventor Charles Babbage, to author a description of his theoretical analytical engine, a proto-computer. This piece of writing would require a vast imaginative leap: from viewing computation as mere calculation to envisioning its broader capabilities for symbolic substitution.

So, in honor of Lovelace’s creative spirit, here are seven fictional Adas for the curious reader, from new classics to deep cuts:

Disraeli’s melodrama shows that Ada had already begun this drift into the imaginary, into myth, in her own lifetime: she was a young mother in her early twenties when the novel appeared. The novel’s epigraph, moreover, is taken from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the narrative poem in which bad-boy Romantic poet Lord Byron first immortalized Ada, his infant daughter.

Childe Byron’s “emotional subtext,” as Linney calls it, is that he, like Byron, had separated from his wife when his daughter was a baby. This daughter would grow up to be the Academy Award-winning actress Laura Linney. In 1982, Laura performed the role of Ada in a Brown University production of her father’s play.

But Ada remains a minor character, a veiled, shadowy presence on the novel’s fringes. There is a constant push-pull between a seemingly genuine desire to honor Lovelace and the early history of women in computing along with an equally strong discomfort with women in the novel’s male hacker space.

Gibson and Sterling portray Ada as simultaneously dotty and debauched, an aristocrat past her prime who has descended into a world of gambling, drink and low companions. This portrait is not exactly slanderous: some biographers have emphasized Lovelace’s penchant for horse-racing, extra-marital entanglements and chemical dependencies. But it is certainly unflattering and incomplete.

Otherwise, the parallels between Thomasina and Ada are rather remarkable. Like Ada Byron, Thomasina is a witty, precocious teenager, verbally adept and also brilliant in the sciences. Like Ada, she begins an affair with her tutor when on the edge-of-seventeen. And, like Ada, she works out key innovations in science decades ahead of her time.

The narrative consists of three interconnected tales: the text of Byron’s lost novel itself, Ada’s annotations, and the present-day discovery and decoding of the recovered manuscript by historian Alexandra Novak, who is in London to research Lovelace for a website on women’s contributions to math and science.

Unlike Linney, Crowley doesn’t depict a physical reunion of Ada and Byron. Instead, it is on the page, and through a marriage of sorts between Byron’s art and Ada’s science (her encryption of the novel), that Ada becomes deeply connected with her father’s life and work.

Into this gender- and genre-bending mix comes the 67-year-old Lovelace, a grand dame of science rather than a “funny little grey-haired bluestocking” (as The Difference Engine would have her). Ada occasionally visits Illyria to make improvements on the analytical engines, then to drink brandy, smoke cigars and gamble with the professors. Think: Ada Lovelace given the Golden Girls treatment.

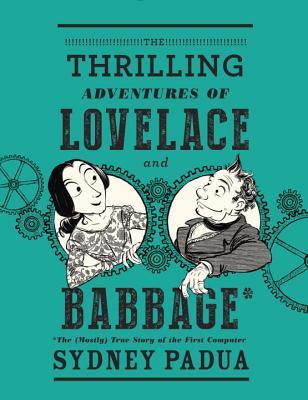

The Thrilling Adventures deliberately frames Ada’s life in terms of a twenty-first-century conversation about both women’s unspoken role in the history of science and today’s dysfunctional tech culture. Putting past and present, fantasy and reality in conversation, Padua shows how we have written – and continue to write – the fictional Ada into being.