Please visit our new site!

Fiction

A literary voyeur

The Tantalus Letters: Part II, Chapter 1

20 January 2007

www.lablit.com/article/202

This week I think you’re going to find out how much physics means to you – whether it’s enough

Editor's note: We are pleased to continue the weekly serialization of an original novel by Laura Otis. Set in the mid-1990s when e-mail was just becoming mainstream, The Tantalus Letters is an epistolary tale of four academics – two scientists and two English professors – caught in a virtual net of love, lust, science and literature.

Part II: Spring

Chapter 1

“You must see that when you write to someone, it is for him and not for you: you must therefore try to tell him less what you think than what will please him most.”

- Choderlos de LaClos, Les Liaisons Dangereuses

8:43 - 11 March 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Owen Bauer

Are you all right? I’m so sorry. I didn’t expect this any more than you did. I want to help any way I can. What can I do? I never even imagined this could happen. Although I also want Jeannie to be happy, my main concern is for you. Are you eating? Are you getting up? Are you going to bed? I wish I could be with you, though I know I’m the cause of the problem.

You know my parents divorced, and I know the pain splashes around everywhere, like a mild acid that only starts to burn minutes after it hits. I really respect what Trish is doing about Jeannie, not wanting to cut her off from the tainted father in a burst of rage.

I was also spared the horror of a custody battle when I was a kid, but for very different reasons – my father just didn’t want to deal with the hassle. He was seeing this beautiful Chinese woman then who was really nice to him, and to me. She used to look at me as though she felt sorry for me. Probably he was telling her my mother was a monster, and that’s why he left her. She had sad eyes. I remember once she gave me this little red packet of good luck money for New Year’s. He dumped her a few months later.

Once my mother got the court order, I hardly ever saw him, just heard from her what a bum he was. Even though I was seven, I never believed it – how could a guy have that much money and let us be so poor, and how could a guy go out with that many women and just leave them? I thought there must be some good part of him that my mother had just never turned on. You know, I still do? He’s an old alcoholic now, too ugly and disgusting to attract any woman. I see him about once a year and don’t tell my mother about it. I’ve never seen any sign of goodness in him, but I won’t give up yet. Maybe he’ll repent on his deathbed or something. My mother just hopes that he’ll die before she does. She hates his guts.

So Trish is doing a wonderful thing here, I don’t know if you realize how wonderful. Divorcing you – well, that all depends on your perspective. I wouldn’t. I think I could forgive you just about anything.

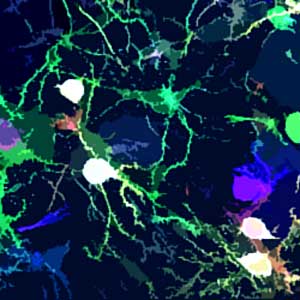

I know I said I’d do anything to be with you, but it’s not quite true – I’m anchored to this lab – no, I’m the navigator, and I can’t leave my console for a minute, or it’ll crash. In science there’s no such thing as auto pilot. From the kitties to my students’ love lives, it’s all on my shoulders. You are what gives me joy, and learning how the synapses form gives my life meaning. We all want both, of course, but hardly anybody ever gets it all. I know that nothing and no one could ever make me give up this lab voluntarily. The NSF or the NIH could divorce me, I suppose – then I really don’t know what I’d do.

This week I think you’re going to find out how much physics means to you – whether it’s enough. I hope it is. And Jeannie still loves you, and she’s still there. As a kid who went through it, I’d advise you just to keep in touch with her as much as you can and keep letting her know that just because you and her mom don’t want each other, that doesn’t mean you don’t want her. Just live, work, write your paper word by word, and know that I am with you.

20:12 - 11 March 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Rebecca Fass

What’s happening with Owen? My virtual love affair is down, so maybe I can live yours, twice removed – virtual and vicarious. Is everything virtual vicarious?

I missed him so much yesterday that when I got out of class I went to the library and got his latest book. We have a lot of them, and I couldn’t believe I had never thought of this before. It was all beat up and marked up and well read, and someone had written the title page that the thesis was on pp. 68-69: Great Expectations is a novel about misreading and about the failure of written language to convey the true nature of human relations.”

I went for the acknowledgements, of course, my heart beating wildly, knowing what I was going to find, again not believing that I’d never thought of this before. His wife’s name is Beth. His boys’ names are David and Jeremy. Misreading Dickens was dedicated “to Beth, David, and Jeremy, whose love warms me in my Hard Times and teaches me how to imagine and to wonder.”

Reading this dedication, I felt like a disease. My heart was pounding with the guilt and excitement of the voyeur. I felt as though I were seeing something I wasn’t supposed to be seeing. It’s crazy – I mean, it’s a library for Chrissake, and anyone who wants can walk in and pick up that book and look at that dedication, but I felt as if I were committing a violation, looking right in their bedroom window. I xeroxed as much as I could as fast as I could, cursing, dropping quarters. This is what I’m going to do for now, read all his articles and his books. I can’t be with him, and I can’t talk to him, but I can still look into his mind. Know thine enemy! I want to crawl all around inside of him, and this seems fairly constructive: it doesn’t hurt anyone, and I might actually learn something.

I haven’t started reading yet, but I peek at that dedication daily. Along with the guilt and excitement, I feel jealousy. Then I feel more guilt for feeling the jealousy. He was with me when he was writing this book two years ago. I know, because he talked about it. What would it take for me to get into that dedication? I bet I taught him a thing or two about how to imagine and to wonder. I bet when he was at his terminal two weeks later, he was typing about writing and human relations and imagining he was having some human relations with me.

I’m going to comb his books for any sign of that. I’m going to read them all like Freud, as if they were all one big dream, one big portal to the nether regions of his mind. I’m going to do research on those regions, and then I’m going to pass through that portal and go there as soon as I learn how. I’m going to walk around the Maginot line.

I wonder what it feels like to be Beth. I wonder how she warms him in his Hard Times and teaches him to imagine and to wonder. They’ve been married about twelve years, I think, and they had the kids right away. I wonder what she does. He’s never talked to me about her, not a word. I don’t wish I were her, though. I’d like to sleep with him and turn him on and inspire him occasionally, but I don’t want to be a wife.

Do you ever think about what it’s like to have kids? You swell up. You get fat. Alien is growing inside of you, and you can’t stop it. You feel sick. You throw up. Your husband isn’t attracted to you, and he goes and sleeps with someone else. I know. I have been this someone else, and so have you. How could you love something that sucks your blood, expands inside of you until you’re hideously distorted, grows at your expense? I would hate the thing from the moment of conception.

Then come fifty hours of excruciating agony, screaming with pain. Maybe they rip your belly open so that you’re scarred for life.

But then it’s worse, it’s there, and you’re its slave. All day long, all night long, it screams and shits, shits and screams. You can’t rest, can’t work, can’t sleep, can’t think. You cease to exist as a person, you exist only to serve the monster and to respond to the screams. The mother-in-law moves in to bully you and tell you a hundred times a day that you’re inadequate. Your house, your body, your life, your time, your money, none of it belongs to you any more. You scheme, you grovel for scraps of time. You rage inside against the monster that’s enslaved you, that you created by mistake because you didn’t know what it would be like and everyone lied and told you how it would give your life meaning. And you have to masquerade and pretend you love the screaming, shitting monster because you’re evil if you don’t. You live a lie. As far as I can tell, everyone lives the same lie, and everyone perpetuates it, in the interest of perpetuating the species. No one would ever have kids if she knew what it was like and could do anything to prevent it.

You hate it, and you hate your life, and you can’t ever express your true feelings to anyone any more. It grows, and as it grows, it gets smarter and senses how you hate it for killing your life. It’s against you from the beginning, and it hates you back, and it just keeps getting smarter and smarter. Along with your husband, it plots to control you with guilt and take away all of your time. If you don’t do what they want, you’re selfish. You can’t work. You can’t go to conferences. People ask you what you’re working on, and you try not to cry. You don’t get your students’ papers back, and you miss your office hours, and they look at you with knowing, accusing, self-righteous disgust as you stammer excuses. You can’t exercise, and you get fat. You can’t use your mind, and it gets fat, too. You become mediocre in every possible way, half-dead. Life rushes by all around you, keen and exciting, and you’re trapped in the miserable little phone booth of your existence, barely able to breathe, unable even to communicate with the outside world because the phone is dead.

The monster keeps growing. It uses all of its intelligence to torment you, because it senses how much you hate it. It watches you constantly, looking for weakness. It laughs and jeers at you when you make a mistake, continually challenges your intelligence and your judgment, tests you, experiments on you, tries to sabotage your work, accuses you, rages at you, curses you, mocks you, tortures you psychologically. It hits the neighbors’ kids, and the neighbors call up to tell you what a terrible mother you are. It does badly in school, and the other mothers talk to you with pseudo-sympathetic, knowing smirks about their children’s successes, saying with their eyes, see, I always knew it, the truth will out, you’re stupid, and you’re a horrible human being, you can hide it, but it always comes out in the kids, like it comes out in the wash. When it gets to be a teenager, it takes drugs, has sex, drops out, runs away. And everyone says it’s your fault because you’re such a selfish person and such a terrible, terrible mother. And then you’re fifty, you’re fat, your body is ruined, you’re exhausted, you’re stupid, your mind is dead, you’ve written nothing, and everyone around you is telling you what a horrible human being you are. That’s what it’s like to have kids.

That’s what it was like in my house, and that’s what it’s like in every house, just people won’t admit it. My father was out of it, off writing books all the time. My mother, we came between her and her music, and there was nothing we could ever do to make up for it. I tried as hard as I could to do everything she wanted, but what she wanted was for us not to be there. My sister went the other way. Do you know she actually once poured an entire jar of honey on the piano keys? They had to take the whole thing apart to clean it, but even then it was never the same. That’s what my kid would do to me, pour a jar of honey on my computer. Like Glenn Close, in the movie – they do that, and they wonder why you don’t love them. They want you to love them, and they throw acid on your car and pour honey all over your computer. Maybe I was always Glenn Close, Glenn Close facing the Maginot line.

Well, from now on I’m going to be logical, rational, reasonable. I’m going on a campaign, goal-oriented behavior. The goal: to be connected. To have him want me, and admit it. To have him think, as he’s typing the dedication of the cell book (Middlemarch, neurons), “to Leo, whose lips and lascivious language have been there for me in my Hard Times and taught me how to imagine and to wonder,” even though he can’t write it. To be joined to him, to be part of him, to live the delight of a connection no one can see. The strategy: to know him, to know what he wants, to fly through every dark tunnel of that honeycombed, wanting mind. What do you think?

22:07 - 12 March 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Lee Ann Downing

You frighten me, Leo, you and your guy, but I know the truth when I hear it. I don’t think everyone sees life the way you do, but you write the truth well, exactly as you see it. Just don’t write it to him, at least not for awhile. He really would blow you away. Reading his books seems like a reasonable idea, as long as it doesn’t take too much time away from your own work.

Whatever you’re saying to Marcia, she thinks you’re the greatest thing ever. You sound ripe to write the rabbit book. I say go for it, start writing! Maybe it could even cross over from academia and become a best seller. I would buy it. All the women in science would buy it.

Me, I feel like I just won the lottery because I got five numbers right, and the woman who got all six numbers right just got run over by a large truck. She’s divorcing him! Can you believe it? Here I’ve been, this vulture circling their marriage, waiting for it to die, and I guess it’s time to swoop down. I wonder if vultures feel any sense of satisfaction. I don’t. I made it die, and now this poor kid has no father. Trish is going to do fine – I like her more and more from his descriptions. Even knowing what he did with me, she’s not going to fight for total custody, so the kid can still have a father.

I wonder if it ever really occurs to people that they’ll win the lottery. I mean, they make plans, all you need is a dollar and a dream, but living with it? I wonder if he’d even want to live with me. I wonder if I want to live with him. He’s a high-maintenance animal, not like one of my cats. I wonder if Jeannie will hate me.

Well, he’s there, and I’m here, and for awhile neither one of us is going anywhere. Marcia, Tony, and Dawn all have data coming in fast, and we need to do something with it all. I’m so worried about him. What if he won’t eat? What if he stops working? You, me, we never freak out, but he could. I have to keep him going somehow. He’s so wonderful.

I feel so ashamed for being glad Trish is fat. Do you think Beth could be fat? I think I could handle being married to Owen. Having a kid, I don’t know. I’m in this lab eighty hours a week and can barely keep things going. I have no clue how other people do it, although they seem to be reproducing. I want a wife, that’s what I want, someone to put dinner on the table every night and take care of the kids and tell me how wonderful I am.

9:15 - 13 March 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Rebecca Fass

Wow, jackpot! Now this is a new one! Forget the mack trucks and the vultures, it’s not as much your fault as you seem to think it is. Remember she’s the one who’s divorcing him because she WANTS to do it, and she sounds like she knows exactly what she’s doing. What did you, rape him at gunpoint or something? Artificially stimulate his brain? He knew the risk, and he took it.

Verbs always say it all, that’s the great thing about making yourself write things down: I seduced him, she’s divorcing him. What is this guy, never a subject? Didn’t he do something to you, and her, too? Poor Owen. I have to admit, he’s pretty alien to me, not my type at all, but for your sake I’ll try to understand him.

Josh, that’s my type – wit, chutzpah, aggression. I miss him so much. If he were a dog, there’d be this big sign up, Beware of Dog. Josh bites. God, I miss him! He bites to defend his home and family against intruders, and that’s me, boy, Cathy in Wuthering Heights, beautiful Merle Oberon in flight, half over the wall, almost out of there, when this great, big, snarling dog clamps his teeth onto her delicate white ankle. I am a bigtime intruder.

I am always the subject, I always command the active verb. To tell you the truth, I’m not sorry about Owen’s divorce. As far as I can see from my own family, there’s nothing particularly good about having two parents anyway. She’ll be all right.

18:57 - 17 March 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Rebecca Fass

I miss Josh. I’ve got his words on paper now instead of on a screen: clear, forceful, direct, brilliant. He writes like Fred Astaire dances – it flows so naturally, so logically, one idea leading effortlessly into the next, but you know it got that way only through years of the most strenuous thinking and rethinking and slashing and despair. I have the secret delight of knowing that during all this grueling rehearsal, at least for the Dickens book, his mind was dancing with me, and I scan it hungrily for hints of unconscious activity.

I think I see it, especially in the sections on interpreting patterns of light and darkness when he gets into pale skin and black hair, but the problem with reading a code is that if you’re cut off from the guy who created it, there’s no way of ever knowing whether you’re right. There’s no feedback except from your own desires, and they’re pushing you to read more and more into it based on the excitement generated by what you think you’ve found. I feel like the eighteenth-century Europeans trying to read the hieroglyphics, poor fools. This is my delusion of grandeur, that I’ve permeated his consciousness and seeped into his work and that even in his books I’m present, a force in his mind and in his words.

I sit here trying to write the rabbit book, my chin resting on my stuffed Lion, Leonhardt, staring at the pink and purple streaks in the west behind the black capillaries of my oak tree. I read his words instead, looking for myself. His words on the screen were better, brief and brutal as they were, because they were glowing and alive, and I knew he’d written them for me. Now there won’t be any more. I can’t stand it.

I begin to understand all these characters I’ve always laughed at, the ones who killed themselves for love – Romeo and Werther and poor little Michael what’s ‘is name in “The Dead” who stood out in the rain and got pneumonia. What’s the point? When I log on now, the silent, blinking dollar sign mocks me, inviting me to ask for mail in the absence of new messages. Or worse, the beep comes, and the announcement, “You have three new messages,” and I grip the edge of my desk and try not to faint, and one is yours (no offense), and two are about changes in the dental plan. No matter how many times I tell myself, face it, woman, it’s over, he’s not writing to you ever again, my heart still speeds up when I hear the beep. I guess I haven’t given up and won’t give up. I think he’s bluffing.

We’ve been done with Liaisons for weeks now, and Valmont has died valiantly, and Merteuil’s soul has become visible in her face. The students still insist these two were different: he just wanted to have sex; she wanted to destroy people. They’re so certain, they almost have me convinced, but there is something very, very wrong with this idea. To write the rabbit book, I have to figure out what it is, but in the meantime we’ve plunged straight into The Red and the Black, and I find myself immersed in the mind of ambitious, angry, calculating, beautiful little Julien Sorel. Julien has always turned me on. When he says, “I will have that woman,” he inspires me.

I am going to have Josh. I am going to do it. I am not going to do anything rash or stupid, but I have a plan. I am going to do a Valmont. I will have him, and it will be my greatest campaign and my greatest triumph. And when I say “have,” I mean it just the way Valmont and Julien mean it – to make love and later to part ways, but with the knowledge that I have made him want me and that I am forever inscribed on his consciousness.

I am going to turn myself into a great, swirling, pink cloud of words like a genie. He’s such a hungry reader, he’ll devour anything, and he’ll never be able to resist or erect any barriers against me. He can control what he lets out, this one, but not what he lets in. After transforming myself into digitized energy, I’ll swirl out from his screen into the living blackness of his eyes, and then, as digitized energy again, I’ll rocket along his optic nerve and explode into his brain in a cascade of sparks. Since I’m a smart bomb, I’ll head straight for his pleasure center. You tell me what to do. I’m going to write my way into his consciousness. Meanwhile, I’ll write the book so as to purge myself of thoughts he won’t want to hear and that I might otherwise let out.