Please visit our new site!

Fiction

Signal and noise

The Tantalus Letters: Part II, Chapter 2

28 January 2007

www.lablit.com/article/204

If you get all those neurons fired up at the back and in the core, he’ll never be able to handle it

Editor's note: We are pleased to continue the weekly serialization of an original novel by Laura Otis. Set in the mid-1990s when e-mail was just becoming mainstream, The Tantalus Letters is an epistolary tale of four academics – two scientists and two English professors – caught in a virtual net of love, lust, science and literature.

Chapter 2

19:15 - 18 March 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Lee Ann Downing

You are dangerous. I mean, there ought to be a law. I’m actually starting to feel sorry for this guy. Just don’t get yourself fired, that’s all I can say. I’m not as sure as you are that he’s bluffing. I would at least wait awhile before sending anything, and if you do (I still don’t think you should), send something absolutely harmless, something the e-mail police could never find fault with. Don’t tell him what color panties you’re wearing. I think you could seduce anyone, though, because you’ve already seduced me, the supposed Voice of Reason.

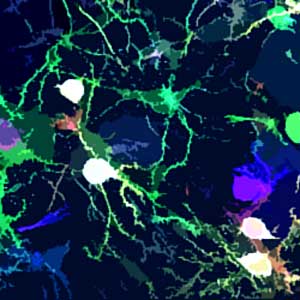

I can’t resist your plan and just wanted to be Mr. Spock (or Uhura? or Sulu? – the voices of science, communications, and navigation all at the same time) and give you the coordinates. Once you get into the optic nerve, go with the flow of traffic into the lateral geniculate nucleus, but then you should split your signal. Part of you should head for the occipital cortex, where you can dance until you create a conga line of all his visual memories of you, but another part of this smart bomb should go on to the thalamus and hypothalamus. Your target is the core, deep, deep inside, the amygdala for emotion, the hypothalamus for bestial hunger, and maybe the limbic system for emotions and smells, all intertwined. Be sure to hit the hippocampus for encoding new memories. The cortex lies on top of all that like a big, wet sponge trying to muffle the wild party going on below, but if you get all those neurons fired up at the back and in the core, he’ll never be able to handle it.

What I can’t predict is what he’ll do when the sponge dries out and blows away. Have you thought about this? When this happens in your books, don’t people get killed a lot? My idea of “having” is different from yours, I think. I could deal with having Owen, waking up in the morning and finding my nose wedged against his wonderful broad back.

20:22 - 25 March 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Josh Golden

Subject: The Life-Line

I hear it every morning and late into the night; the chugging and scouring, the warning hoot to get ready, get ready. It hasn’t changed in the 33 years I’ve lived here: the ugly, dependable, inevitable blue and yellow beast that carries us into the city. The view through the windows is scratched and dim, barely revealing the tiny red brick and white wood houses that fly by, identical, one after another. At night there are only lights and your own face in the window, white, ghostly, with deep shadows under the eyes.

In the morning between six-thirty and eight there’s a gradient of people, mostly men, hurrying to the beast the way they hurry to the shaft in a Welsh mining town. The women wear high heels, and you can see that their hair, in great masses of curls, is still almost wet; the men wear woolen coats and carry briefcases. They clog the bagel shop, listening for the bright, demanding chord, and they climb into the machine and vanish, only to be followed by a second swarm.

Sometimes a foot of snow will stop it, or more often ice, but never for long, the life-line between the people and their work. They tumble out at Jamaica, dirty, icy nexus, where they dash through trains to reach their own lines and curse the cold in fine clothes that won’t keep it out. They try their best not to press up against each other in trains that smell of burnt wiring and bitter heat and where there are never enough places for them all to sit. The fathers do it every morning and night for forty years, and then the sons and daughters start, with a newfound sense of importance in their suits and their talk of the real world. Jamaica is the real world, waiting for the clicking, humming electric creature that will carry you to your final destination once the scouring diesel has brought you this far.

The train that carries us to the real world brings fear; it is too big, too strong to stop. It hurtles through little stations, rushes past the flashing zebra arms of crossing gates, and though it sometimes falls off, it will never stop; it will run over everything. It always flattened the pennies we left on the shining silver rails. We knew it would roll over us if we let it, and our mothers told us never to go near the tracks. We did anyway, of course, and there was the thrill of danger as we balanced on the rails and listened for the warning chord. We ran screaming when we heard its snorting and saw its yellow snout appear.

In high school I used to write poems. I haven’t any more until very recently, when passion brought back my voice. I had a fan, then, my friend Jodie’s big sister Charlotte, who had “problems.” Jodie would have parties for us, her life force asserting itself despite her alcoholic mother and Charlotte’s shadowy pain and the house crammed with books, papers, mildew, and dust. We gathered there, and we talked and danced. Sometimes I played their piano and we sang. I loved Jodie and the way she defied the misery around her.

Jodie loved Robbie, the anchor of our group. At seventeen, he had the kindness and wisdom of a man much older. He and Jodie worked side-by-side, campaigning, laying out the yearbook, laying out the paper, laying out the literary magazine, sometimes all night, yet he never wanted her the way she hoped he would. She was not beautiful, not to look at; only her strength was beautiful, her will to go on in the midst of madness.

When he starting seeing this Thai exchange student, she almost lost it. I think he knew about her desire, and he tried to be as kind to her as he could without giving up his own. Once we were all on this field trip, and we were at Jamaica waiting in the cold. Lovely Jin, that was her name, was leaning out over the platform, looking out at the approaching train, and I saw Jodie behind her, stepping slowly forward, thick, strong arms tingling, itching to give one terrible, effective push. She didn’t, of course, but I could feel it with her; it would have been so easy and so satisfying.

Both Jodie and Charlotte cut themselves, and on their wrists were the straight, white worms marking the times they’d tried to open themselves and let their lives flow out. We took turns stopping Jodie, who would always warn us somehow when she was going to do it, but Charlotte was harder, because she stayed alone in her room most of the time and had no friends. At parties she would slip out of her room, and she would look for me. She would wear a limp maroon bathrobe, and her brown hair would be half in a ponytail, half out. Her black eyes would glow with pleasure as she told me in her whispery voice how she loved my poems. I would tell her thank you, and she would ask when I was going to write some more.

It was Robbie who called to tell me what had happened. In the end, Jodie hadn’t been able to stop her: Charlotte had gone out for a walk in the early morning and had laid herself down crosswise on the tracks, resting her head on one shining cold rail. The blue and yellow monster and its load of commuters had run right over her just as she’d wanted it to, and they’d never felt a thing. Someone called the police only later, when he saw what was left of her. The train had separated her head from her body.

I wrote poems after that, but they had no force to them. Finally I stopped, and I began again this year, when I suddenly found the words to say what Tantalus was feeling.

There is nowhere here where you cannot hear the insistent chord of the approaching train. There are so many lines, so many people who need to pass along them, in and out, in and out, the respiration of a massive creature terribly alive. I hear it now in my office and in my bedroom at dawn, the demanding voice of life in motion, running over everything in its path.

12:14 - 31 March 1997

From: Marcia Pinto

To: Lee Ann Downing

Hey, what’s been going on? What’s happening with the book? Serving as a data point is giving me so many ideas, now I have to transmit them spontaneously. So, are you saying men keep making all these movies about women who won’t disconnect? There’s really something to that, the recurring story of the woman who won’t go away. You’ve got something here. She won’t go away, and if you ignore her and hope she’ll go away, she gets madder and madder, trashes your car, trashes your pets, trashes your marriage, shit, she trashes the whole town.

What I’m really wondering is what the male equivalent is – I mean, is there a female version of this story? They’re different. I can’t think of any story about a spurned male lover who won’t go away. What you get are stories about these psycho-types who hunt you down and try to kill you when you try to leave them – Sleeping with the Enemy, you know, the controlling husband determined to regain control over poor Julia Roberts. It’s close, but it’s different. What do you think is the difference?

What about your life? Are you going to put your life in the book, too? I am still eying the tetrodotoxin.

18:03 - 31 March 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Lee Ann Downing

What are you transmitting to your cyberlover? Be careful! I can picture him licking his chops – I know you love that – but don’t let him sink his teeth into you. How about running it by me again? I could use the entertainment, and I love reading your stuff. I wish someone would write to me the way you write to him.

I’m doing a lot these days – know what’s amazing? Marcia and Dawn have got this project going that shows that if a kitty grows up in the dark, with his little eyes covered, the connections still form almost normally with the cells in the visual cortex, but if you block the activity of the retinal neurons with poison, so that they can never fire at all, they never hook up with the cells they’re supposed to talk to in the brain. They must be relying on some sort of noise that happens whether or not they’re seeing anything. We’ve got to get this out, and soon, so I’m taking Marcia back from you for awhile.

19:22 - 4 April 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Josh Golden

Subject: Noises in the Dark

My friend Rebecca the neuroscientist says that retinal cells can still form connections with neurons in the brain, even when you’re blindfolded and can’t see anything. Apparently they make noises even when they can’t see, and as long as the noises are there, they can hook up with the cells they’re supposed to. It’s only when you poison them so they can’t say anything that they can’t make the connections.

Tomorrow is opening day for the Mets. The forsythia is turning the parkway into a chute through yellow canary feathers, and the trees are purplish at the tips. In the morning we are still shivering, but the force of the thing is inevitable: more light, more heat, the momentum of biological time.

What is it like to have children, Josh? My friend Rickie had a baby once.

Rickie’s real name was Rachel Rubin; nobody knew why we called her Rickie, not even me, and I’m the one who started it. She was my friend as long as I can remember. At the bus stop, this idiot Bobby Deegan would always make fun of her. RU-ben, he would say to her, RU-ben, yawruh JEW. She would look down, and her face would get very red. I would go over and stand by her. I didn’t titter like the other kids. I hated Bobby Deegan.

Hearing about the Mets, I always think of Rickie. Her father used to take us to Mets games, a whole group of girls, and beforehand he would take us to a Chinese restaurant in Queens so that he could eat. He was really fat, and at home her mother wouldn’t let him. With us he would eat great round heaps of glistening meat and strange vegetables and let it all settle in his stomach under a sweet blanket of ice cream. We would have to promise not to tell. It was so great. Sometimes the Mets would win.

In 1979 Rickie could drive, and it was just us two, careening down the Grand Central Parkway, jumping from station to station in search of the song “Fame.” They played it so often, you could always catch a new piece of it as soon as one rendition was over, and so we followed it, a never-ending splice of inspiring tune. I can’t remember if the Mets won that day. All I remember is climbing on the seats to reach down to Felix Millan so he could give us his autograph. They were wet, and this lady got really mad at me for leaving black, watery blobs where she was going to sit.

That night we went to Rickie’s sister’s house, somewhere in Queens, and we ate at a diner that had little dishes of red jello revolving in the refrigerator next to the six-inch strawberry cheesecake. Rickie’s sister was cool. She had been to college, and she was married and talked about the importance of marrying a Jew. She rolled a joint, and we listened to the Kinks. She complained about the way they’d printed up her resumé.

Next day she took us to a party at a big house in Roslyn, surrounded by an endless green lawn. Rickie was anxious – there was this guy, and she was wondering if she was going to see him there.

I was always so fascinated by Rickie. She was huge on top, every man’s dream, thick, wavy black hair, big brown eyes. Me, I was this little scrap, and she was a whole meal. She beat everyone, in gym, at the flexed arm hang, this thing where you had to curl your fingers and cling to a bar and hang on like a drowning animal as long as you could. All her weight was in her upper body. She was real good at that, just hanging on.

Her mother had always been crazy. The whole temple knew it – she was always envisioning these huge projects that would make the world feel the true spirit of Judaism, then calling up the Rabbi to tell him about them in the middle of the night. I remember once when I was at her house hearing a terrible fight between her and Rickie’s sister. It was so insane: the sister claimed she’d washed her hands, and the mother swore she hadn’t. “That soap is as dry as a bone!” I heard her screaming. Then came the sudden, sharp sound of slaps, followed by more screams. “You LIED to me!” shrieked the mother. The sister just screamed back that she hated her. Rickie got very quiet and wouldn’t say a word. I remember how upset she got once when she saw a mother slapping her little girl in a supermarket. She was so quiet, she hardly ever said anything, but I remember her saying how terrible it was to hit a child.

When her mother called, I don’t know where Rickie was, but whoever answered looked around, didn’t see her, and said, “Rachel can’t come to the phone right now.” Her mother lost it bigtime. She was sure Rickie was off somewhere having sex with this guy. They all knew about it, I realized afterward, the mother, the sister, Rickie herself. It was him, the guy who lived there on that endless green lawn. You see, he wasn’t Jewish.

When Rickie spoke to her mother, I saw the joy drain from her face and from her spirit. We had been so happy there listening to the music, wandering from group to group. Now on the way home, we left the radio on one station, and we hardly said a word. I went in with her, thinking her mother would go easier on her that way; instead, she screamed at both of us. “Young people today ah SHITHEADS!” she screamed. “Yawr all SHITHEADS!” She yelled about the perils of “intuhdating.” Intuhdating led to petting, and petting led to the worst evil of all, intuhmarriage! I wasn’t used to this; my parents never raised their voices, only stroked you with a brush dipped in acidic guilt that ate into you slowly forever after. I felt my throat getting hard and tight, my head filling up, ready to explode. I was shaking. “You – you don’ look good,” her mother said to me finally. “Don’ make huh cry!” Rickie burst out angrily. I couldn’t help it. I cried. I always cry when people scream at me. I was even vile enough to stroke Rickie with guilt afterwards, telling her that no one had ever spoken to me that way in my life. I’m sure she thought it was her fault, and I let her think it.

I didn’t see Rickie much after that. I was at Stanford, and she went to Nassau Community College. Then when I’d graduated and come back from six weeks in France, she came to see me. “She’s about nine months pregnant,” my sister said. It was Rickie, sure enough, still beautiful, still with her shy giggle, enormous and about to burst at any moment. She didn’t know who the father was. “Oh, I’m wild now, you don’t know,” she told me, and she threw back her head in a crazy laugh. She had stopped getting her period, she told me, but she had thought that she just, y’know, wasn’t getting her period. Then her mother told her, “you look like you’re about five months pregnant,” and she was, and it was too late. She was going to give it up for adoption. Her mother had arranged for it to go to a Jewish family, and she was pushing the hospital to put it down as the removal of a growth so it wouldn’t go on record and prevent her from marrying a nice man someday.

I was busy, getting ready to start grad school, and I missed her delivery about a week later. She showed me a picture of a very red little thing with a great quantity of black hair, plastered down over his sticky head. “It was a boy,” she said, “the most beautifulest baby boy you’ve ever seen.” I showed her my pictures of France, and she asked me quietly if she could see the picture of the synagogue one more time. That was the last time I saw her, and I’ve always wondered what happened to Rickie and her most beautifulest baby.

The light is golden now, my favorite part of the day. Are you out there, Josh? What’s it like being a Jew? I’ve tried so hard to understand. All of my friends always belonged when I was growing up, except for me. The mothers would scream at their sons when they asked me out, and no matter how much time I spent with everyone, there was always this difference. I loved them all so much, and I think they even loved me back a little, but somehow I was always the intruder. Twenty years and I’m still at it, still reaching, still daring. Same yellow canary plumes on the parkway, same Mets, same Passover, same spring, and me, still out of place.

So many guys have told me I’m incapable of love. I can’t imagine what it’s like to create new beings, to live with someone for a lifetime. I do know what it’s like, though, to be connected and to know you should be connected. That connection can be many things; it can create wonders, and it needn’t hurt. Please, please, let me transmit, let this connection live, it can’t hurt, it won’t hurt.

The light is pinkish now, dimmer, and I no longer trust myself to write, the images are so strong. “Jewish women light Shabat candles, 18 minutes before sunset, 7:14 in New York City, in merit of Raizel Gutnick,” it says in tiny letters at the very bottom of my New York Times today. It is time. I imagine them glowing on your dining room table. I imagine you smiling, laughing in the fading light, the same light withdrawing from this café window tonight, these limp red silk flowers a feeble reflection of your candle’s glow.

Live well, Josh, you always live well, and I will live, as I always have, in my own way.