Please visit our new site!

Fiction

What makes you get up in the morning

The Tantalus Letters: Part II, Chapter 3

4 February 2007

www.lablit.com/article/210

All day and all night I splice together the memories and sensations into a designer virus

Editor's note: We are pleased to continue the weekly serialization of an original novel by Laura Otis. Set in the mid-1990s when e-mail was just becoming mainstream, The Tantalus Letters is an epistolary tale of four academics – two scientists and two English professors – caught in a virtual net of love, lust, science and literature.

Chapter 3

18:32 - 7 April 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Marcia Pinto

I’m sorry to have stopped with the questions, especially after you told me your own story. You have been an inspiration, and I have been thinking about this book somewhere in the back of my mind.

You’re asking what’s the difference between Fatal Attraction, Glenn Close leading the terrified kid onto the roller coaster, and Sleeping with the Enemy, Julia Roberts’ control-freak husband feeding her blind old mother her dinner. You’ve hit on the main problem, of course: how to be fair to the guys.

Even though I may yet call it Boiling the Rabbit, I don’t want it to be a man-bashing book. I want people to be able to learn from it. I want to make people think. It’s so stupid just to write off half of humanity, over three billion people. With your help, I want to show everybody what kinds of stories we’re writing and what they’re doing to us. When I can answer your question, I’ll be able to write a book: a theoretical chapter, a chapter on Liaisons Dangereuses, a chapter on The Crucible, a chapter on Fatal Attraction. In my business we always know what chapters we’ll be writing before we know what we’re going to say. That’s where you come in – helping me figure out what I’m going to say. Is this parasitism?

The difference between Fatal Attraction and Sleeping with the Enemy seems to lie in the titles. We’ve got to be fair here: there are movies about both male and female psychos stalking people they think they’re in love with. The male ones tend to be husbands and boyfriends, though, who’re trying to get back a woman who’s run away. I can’t think of any movie about a man who goes crazy and harasses a married woman to death because after one night, he’s fallen madly in love with her. They don’t do this; at least we don’t watch them doing it in the movies. In the movies they have more pride: they take what they can get, and then they move on to a new one.

Suppose you switched the titles. “Sleeping with the Enemy” would work just fine for Fatal Attraction: you can see that he and Alex are enemies almost from the start, as if they’re competing for something and only one of them can have it. But “Fatal Attraction” doesn’t work for Sleeping for the Enemy, because it’s not about attraction at all. It’s about an unusual situation, a poor, sweet girl trying to escape the slavery imposed by a psychopath who never comes across as ordinary. Fatal Attraction was designed from the outset to be the story of Any Guy, who feels an attraction Any Guy can feel, and who makes the “fatal” mistake of indulging it with someone who for a time appears normal. I have to keep thinking about this.

The book’s been deferred lately because I’ve been thinking about this friend of mine and her guy, who’s worrisome because he doesn’t fit into these patterns, if that makes any sense. He’s married, and my friend was with him once four years ago and once three months ago. He told his wife, the jerk, and she left him and took their little girl. What’s worst is that at the same time, he may be losing his job. My concern is not for him but for my friend, who’s very susceptible to guilt. He’s not like the guys I’m used to (or you, I bet) – he seems to need companionship and support to stay alive, and my good-hearted friend may spend all her time providing it instead of doing the work she needs to do to survive. Is this fatal attraction? Seems more like female attraction. She just keeps saying how wonderful he is, and I try not to laugh loud enough for her to hear. What would you tell her?

And my own life? My own life is always in everything I teach and everything I write, like a perfume that permeates everything that’s yours and that only other people can smell. I take it you’ve smelled it. Yeah, there’s a guy. Yeah, he’s married. Aren’t they all? Two kids, boys, computer wizards like him. I see him once a year at conferences. Yeah, we’ve done it. I’m afraid to activate the cascade of praises to him that rushes down through my mind all the time, but, oh, boy, here I go, he’s brilliant, he’s hilarious, he’s written five books and twenty articles, he’s such a good writer it scares you, he works the words like the Language God, and he always knows your thoughts before you know them yourself. For awhile we wrote, and it was like the Vulcan mindmeld, but I wrote too much, or maybe he just didn’t like my mind, and now he thinks I’m Glenn Close. You get the picture. How does tetrodotoxin work?

19:30 10 April 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Lee Ann Downing

A good day today. At group meeting we decided that Marcia and Dawn have enough data to write, and that guy Jacobsen called from Marin’s lab – he really is going to do a postdoc here starting in August, and he’s flying out here in three weeks to check out our set-up.

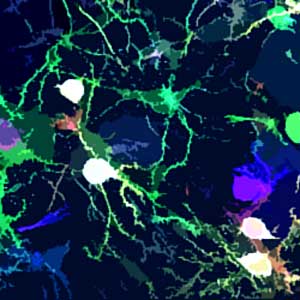

I’m struggling to keep my mind on all this, grappling with my concern for Owen. The picture of him out there all alone is now permanently turned on in my head. Anything else I envision pops up on a corner of that screen, like on those expensive TV’s where you can check out one channel while watching another. I am tuned in, permanently, to the Owen channel, with little cat neurons reaching out to each other in the corner of the screen.

How is the Josh situation? You’re not doing anything crazy, are you? How is your book going? Whatever you feel for this guy, could you somehow channel it into your book?

18:12 - 11 April 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Rebecca Fass

Channeling, that’s not the word: writing when you feel this way is more like telling your mind it has to be a dam holding back a million billion tons of water. The dam has one pinprick in it, and through this you have to let the water emerge in one perfect, needle-fine, linear spurt. It’s much easier not to let anything through at all.

The trouble is avoiding clichés, which gets harder the more water you have to hold back. Remember that guy Dieter in college who was like the cliché police? He’d listen carefully to everything you said, and then he’d snap, “that’s a cliché!” whenever he detected one. After awhile you couldn’t talk at all. What made me maddest is that he never expressed himself in any way that was even mildly interesting. At some point, though, I incorporated Dieter into my head, and whenever I write, there he is, listening, listening, interrupting me to crow triumphantly, “that’s a cliché!” It’s like he thinks he should get a prize whenever he finds one. The words that get through the Great Dieter Dam run pure enough, but they lack the force of that million billion tons. If I’m going to write a decent book, that’s the force I need to summon.

Yet all I do is write. Every thought that comes through now is directed to him, a message I write in my head. I write notes for the rabbit book, notes for teaching other people’s books, I write e-mail, I write in my diary. My sensations become messages as soon as they register; my memories become messages any time they bubble up, and all day and all night I splice together the memories and sensations into a designer virus that I hope will set off uncontrolled production of memories and sensations when it infects his mind. Just imagine if Glenn Close worked for Genentech!

But what I’d love best would be if I could transmit to him directly from a chip in my mind, like Molly in Neuromancer. Remember that science fiction class we took together? That’s how we got to know each other, isn’t it? I thought you were so cool, how you always related things to the way the brain worked. Could this work? Could I send him my feelings directly from a chip in my brain, have him jack into me and live in me sometimes, seeing everything as I see it and feeling everything as I feel it? Without my having to be a Great Dieter Dam, and turn it all into writing? I wonder if he could take it. He’d recoil like Spock from the Horta who was in agony. It hurts to hold back a million billion tons of water.

20:09 - 14 April 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Josh Golden

Subject: Losers

Rhonda always used to say she didn’t want to be like her parents; her parents were losers. Her mother taught sociology, and her father taught math. Neither one of them got tenure, and they ended up picking up courses here and there at community colleges. Her mother finally left academia altogether and went into personnel work.

Rhonda’s father was a superannuated hippie with bushy hair and a beard. He and her brother, a math genius, would always do drugs. They would invite all the guys over who were good at math and physics and computers, and they would all do drugs together. That’s what he loved, filling his house with brilliant sixteen-year-olds on drugs. I used to go because my boyfriend used to go, but I never did any drugs. It was a weird house, stacks of books and papers everywhere, barely any furniture, just this huge scrap metal statue of a dinosaur and a refrigerator with nothing in it but beer.

One night when her father had had a lot to drink, he sidled up to me, and I could feel his moist, beery breath on my neck and his bulk pressing against me from behind, and he said, “hey, darling, wouldn’t you like to come upstairs with me and warm my bed for a little while?” He stroked his hand over my forearm like a big crab crawling up a Rodin nymph. I was fifteen. I think I smiled when I said no; I should have punched him right in his mathematical balls.

From then on I liked Rhonda better. Nobody could stand Rhonda. When she was ten, she told us she was going to Caltech and she was going to major in physics. She had to beat everybody at everything. The guys hated her guts because she could do math and physics better then they could; the girls hated her guts because she put them all down.

As she got older, she got more and more gorgeous. Her body seemed to be made of bronze. She went running and did aerobics five days a week, and she had the kind of body guys dream about, Lena Olin, big on top, no hips to speak of, and legs that never end. She somehow found clothes for nothing that made her look amazing and very mature.

She took all AP courses, got an 800 on her math SAT, 700 on her verbal, but she explained that she’d never felt any affinity for “soft” fields which didn’t reflect real intelligence. As a writer I was beneath contempt for Rhonda, like the guys foolish enough to let their hormones take over and try to put moves on her. She would tell about these episodes in detail, laughing her head off.

Toward the end of senior year she got this crazy idea in her head to sing in the talent show. She got up on stage in a merry widow and looked so good it was almost frightening. She was a great singer, too, but as far as we were concerned, it was payback time. “Boooooo!” we howled, hundreds and hundreds of us. Little math nerds and sweet jockettes came alive at once, screaming at her to get off the stage. She just put the mike up to her mouth and swiveled her hips and laughed at us, and sang louder, over the boos. She was singing “The Time Warp.”

When she was 17 she got into Caltech, early decision. She bragged about how she would be warm when we were freezing our butts off in the Northeast. New York was for losers. Her whole life was an attempt to prove she wasn’t a loser like everyone else: her science, her body, and someday her marriage and her kids.

She liked men, just hated most of them the way she hated most women. I always wondered if she would ever love any guy. Maybe at Caltech, but it would have to be a guy who looked gorgeous, had established himself in his field, did hard science, was hard to get, was hard all over, in fact, and who wanted to live with a one-woman war on softness. I heard she was with one of her professors for awhile until he dumped her. She would never talk about it; that at least had changed.

Her brother avoided academia altogether. Maybe the drugs helped him out. He’s made this incredible amount consulting, I’ve heard, but I don’t know what happened to her. Sometimes I still see her father bicycling, and I shudder.

Lots of things remind me of Rhonda. She’s a voice I never got out of my head, disgusted, mocking laughter at anything imperfect. She’s like that killer robot on Star Trek that got its instructions crossed when aliens rescued it and reprogrammed it. It had been a probe to search for new biological life forms; the aliens wanted it to sterilize soil samples and seek out errors in computer programs, and it ended up seeking out new biological life forms and sterilizing any that were imperfect. In the end Kirk talked it into self-destructing when it was forced to admit it had made an error. I always felt sorry for the thing, the changeling, Kirk called it. I was rooting for it for awhile there, just as I was rooting for Rhonda even as I booed her. It just wanted to wipe out all the losers. Sometimes I feel like that probe, floating out there all alone, half smashed by asteroids, with aliens fingering my circuits.

Are you out there, Josh? I miss you. I am harmless. I wouldn’t ever hurt you or anyone.

12:37 - 18 April 1997

From: Owen Bauer

To: Rebecca Fass

Thanks for being with me through all this. It’s a tremendous help, knowing you’re out there somewhere in your lab, with all your cats and those beautiful hands of yours fingering the keys.

You know me too well. Physics is not enough, never has been, never will be. Whatever force it is that makes me love doing it isn’t enough to make me want to get up in the morning. I have gotten up this past week and shown up when I’m supposed to show up, and written things down that sound something like an article.

I told Dave right away – I had to, and he’s been sympathetic. He thinks she’ll come back, and he’s reading over what I write every day – writing it himself would be more like it. We’re trying to hide the divorce from Rhonda. Whereas a lot of bosses might actually like it (no wife and no kid means twice as much energy for physics), we both have this gut instinct that she’ll hold it against me – the final piece of evidence that I’m a sinking ship.

You know me well enough to know that’s how I feel. Work for me means existing, surviving – the meaning and purpose you speak of, as well as the joy, for the past four years have come from my daughter, and before that from Trish and her faith in me. She’s lost that faith now, for good reason, and I’m left wondering why anyone should ever have any faith in me again. I’m afraid to ask myself why you do. I want to be as good to all of you now as I can – you, Trish, Jeannie – Rhonda! – all of my women – given the terrible mistakes I’ve made. One thing you can be sure of is that you know everything just as it is. For some time now I’ve been incapable of hiding anything from anyone. It’s really only a question of time before Rhonda finds out. In answer to your questions, I do eat, go to bed, and get up. I just never know what I’ve eaten five minutes later, and in the night, instead of sleeping, I think alternately of Trish and of you.

There are a lot of other things to think about, too. Trish made good money, more than I did, and I’m going to have to move out of this place – I can’t pay for it myself. Hopefully this article will mean my fellowship will be renewed, but there’s no guarantee there; it really depends on what Rhonda has to say about me. If it doesn’t come through, I’m unemployed, and I’ll have to think about what other kinds of jobs I can do. I suppose I could be somebody’s technician, or I could do something with computers, or I could do something really different and try teaching physics somewhere. I think I’d like that. I do like what I’m doing now, though, or pretending to do – oh, no, she’s coming, gotta

7:48 - 21 April 1997

From: Rebecca Fass

To: Lee Ann Downing

How are you? Owen is hanging in there, just barely. His boss, Rhonda, seems to want him out of there and may be divorcing him from his job on top of everything else. This woman intrigues me. She really seems to hate him, for reasons I can’t fathom. How could anyone hate Owen? It would be like hating ice cream, or hating the earth.

18:06 - 21 April 1997

From: Lee Ann Downing

To: Rebecca Fass

Her name is RHONDA? Listen, this is really crazy, but I may know this woman. I know a Rhonda who went into physics, and how many of them can there be? If it’s her, he doesn’t have a prayer. Not to be rude or anything, but I can see how someone could hate Owen – all love, no control. I have a feeling I shouldn’t look at this one too hard. But seriously, ask him what Rhonda’s last name is – or no, ask him what she looks like.